NEW YORK — Last September, after much fanfare, waiting, and pomp and circumstance, Style.com was relaunched…and then promptly shut down this week. The plug has officially been pulled, and we’d be lying if we said this was a shocker. Since debuting, we’d heard very little (either good or bad) about the site, which should’ve been concerning given the Condé Nast backing and the universal blessing of the fashion press.

Is this a referendum on legacy players’ clumsy miscues in the new online world — one that modern luxury upstarts are naturally deft at navigating? Maybe. Should we be surprised to watch Condé Nast run full speed into a brick wall — in full view of a watching audience? Probably not. What we do know with certainty, however, is that one report — ironically from WWD, a former Condé Nast title — basically predicted this result back in 2015. At the very least WWD illustrated the internal anxiety and friction within existing publishers in how to best tackle the shifting tide in modern publishing: the lack of gatekeeping influence, and the digital divide.

In investigating the intersection of publishing and e-commerce, WWD, the fashion industry’s oldest business source, asked a timely but simple question: Will this combination ever work? A fair question — and one that had already been addressed, as we’ll get to in a moment — but the more serious, underlying question WWD seemed to be circling was this: Will this strategy work for established fashion publications like themselves — will legacy players like Condé Nast, Hearst, and Time Inc. be able to pull it off?

Good intentions, naive approach.

For existing fashion magazines, the fusion of e-commerce and publishing continues to be an enticing opportunity that promises to offset declining subscription rates and create better leverage against a growing wave of new digital competitors. The intentions are there, yet the thought process, and operational strategy, seems to be rather naive. ‘It looks easy enough,’ they seem think to themselves. ‘We’ll just open an e-commerce page, stock it with big names, and our readers will flock to it. It’s got our name attached to it after all.’ As Condé Nast has now found out with Style.com, it’s never that easy. Effectively, the numbers just weren’t working for them, and worst of all, they were never even able to roll out the site in the US — a huge oversight.

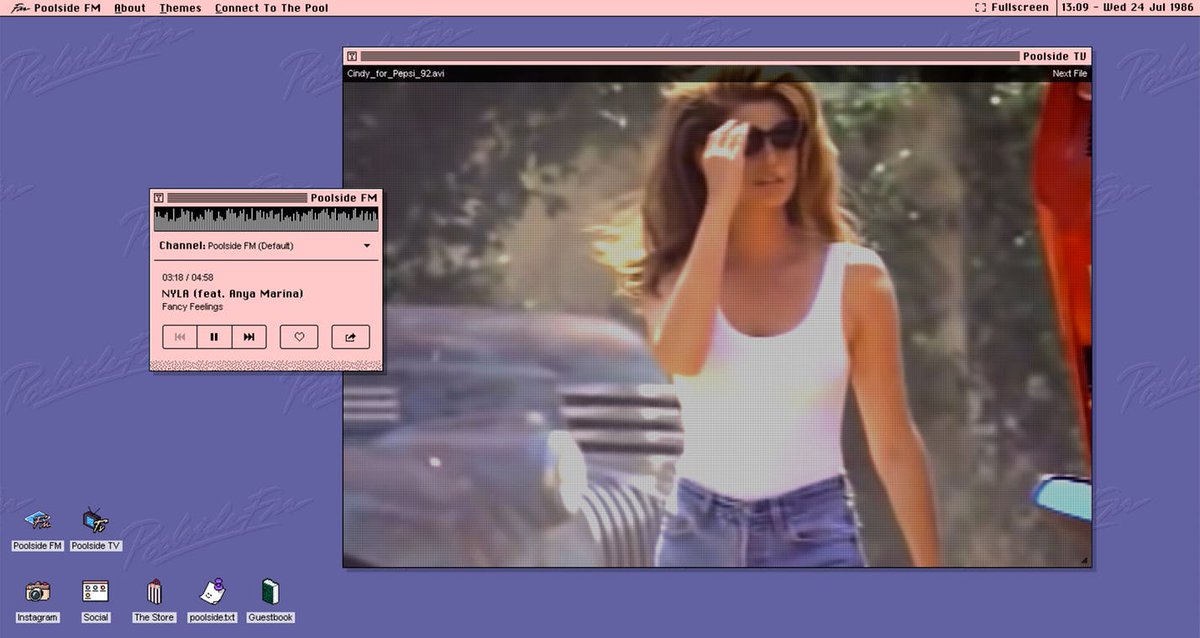

It should be interesting to observe whether this content and commerce idea, in its various forms, will succeed for publishers if it’s created in-house, rather than acquired. Indeed, as fashion publishers continue searching for a future-proof formula, you’d be misguided in betting that the publishing model of the future will originate inside the halls of Condé Nast or Hearst, as earnest as their attempts to adapt may be. Why this skepticism? The fashion industry, if you haven’t noticed, is experiencing something of a dark age period at the moment. Its established brands lack true game-changing ideas, perhaps even the wherewithal to implement them (many are still, in 2017, just now entering the e-commerce stakes), and this affliction certainly extends to even its most cherished publishers.

Hampered by tradition.

Even worse, many of these titles are still tied to fashion’s traditional pattern of behavior. This includes prioritizing their own branding prestige over making the experience fully consumer-centric; adopting an austere, detached tone — both visually and in copy — which isn’t as effective with today’s shopper (the veil has been lifted, and they’re not buying the mystique any more); shallow editorials that do not make much of a play to intelligence; not to mention, the recycled stories, photoshoots, and advice. For such a creative field, fashion publishers play a remarkably conservative game. This may come across a somewhat benign observation, but it’s an important one on matters of innovation.

Publishers might have to acquire, rather than develop in-house.

The impact of this complacency and publishers ongoing missteps are revealing. Since mid-2015, Condé Nast has enacted a round of layoffs at multiple titles; it folded the editorial portion of Style.com in order to remake it into an e-commerce destination (and that turned out great); it shuttered Details, its progressive men’s fashion title; and it also folded Lucky, which was its most significant experiment with publishing and commerce at the time, and an embarrassing failure. Hearst, meanwhile, also seems to be searching for the right alchemy online, with positions in constant flux.

A number of independent publishers — Monocle being the most prominent example here — have already figured out the publishing and commerce formula, even though they are quite niche. You can read more about what they’re doing in a previous report of ours from February 2017. Likewise for a more critical view of where Condé Nast is going wrong, read Skift co-founder Rafat Ali’s ongoing criticism of Condé Nast’s handling of Style.com, dating back to September 2015.

The intersection of publishing and commerce may end up finding a way to work together seamlessly for existing titles, but it will take outsiders not clouded by the old way of thinking, to introduce the real model of the future. It won’t be Conde Nast, and it won’t be Hearst.

In the words of an anonymous media buyer: “…at a time when the industry and market are ‘changing at neck-breaking speed,’ Condé Nast is ‘consistently one step behind.'”